For 40 years, the province has put industry ahead of endangered species

Is the Alberta government hell-bent on eliminating what remains of the two caribou herds that live in the mountains just north of Jasper National Park?

Looking at the province’s recently released draft management plan for the Upper Smoky area, one might think that is the case.

Let’s set this up: the motivation behind the sub-regional plan in the first place was to convince the federal government that the province was doing a good job of caribou conservation. Spoiler alert: they haven’t!

Meanwhile, I can’t help but think of the irony that in these tense times of cross-border tariffs and annexation threats, the company which stands to benefit the most from Alberta’s draft plan is a U.S.-based forestry corporation, Weyerhaeuser. A map of proposed cut blocks in the Upper Smoky shows that Weyerhaeuser plans on clearcutting what remains of the winter ranges of both the Narraway and the Redrock-Prairie Creek caribou herds. Predictably, that has sent off alarm bells for conservationists and people who give a damn about Alberta’s endangered species.

For decades now, provincial governments in Canada have been promising to conserve and rehabilitate caribou habitat. And for decades, those governments have not made good on those promises. As far back as 1978, provincial biologists and conservation organizations said in their Caribou Management Outline for Alberta that “the government must no longer delay action that would reverse the long-term causes of caribou decline” and that “a regional access management plan for industry and recreation must be created.”

Four decades later, we’re still waiting for action.

Circle of life

As discussed in previous Jasper Local articles, for caribou to have a chance, they need some space. They just want to be left alone! Fast-breeding animals such as elk, moose and deer all thrive in open areas or young forests (either after a fire or a clear-cut), and those ungulates’ proliferation is followed closely by the hungry wolves which feed on them.

Mountain caribou, on the other hand, breed slowly and live in higher elevation old-growth forests, or alpine meadows. They live in those areas in large part because that’s usually where the wolves aren’t. Moreover, instead of eating the fast-shooting shrubs in a young clear-cut, caribou eat the slow-growing lichens on the ground, trees and rocks.

Before the resource industry started fragmenting habitat, there was a mix of old and young forests, and plenty of space for all species; caribou had no problem staying away from the deadly shrubs-moose-wolf combo.

Today, however, old growth forests are in short supply because of clear cutting, petroleum extraction and forest fires. For governments, the tricky bit of saving caribou is how to conserve enough of that precious old growth forest while paying heed to the industries which economies and jobs are built on.

Helicopter parenting

In Canada, the provinces are responsible for managing wildlife—except for endangered wildlife, and wildlife on federal lands (like national parks). Even for endangered wildlife like caribou, however, the federal government usually only provides direction in the form of recovery plans; it is up to the provinces to actually make them happen.

Unless, of course, the feds believe the provinces aren’t getting the job done. In that case, then they can step in with what’s called an emergency protection order (EPO), under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA).

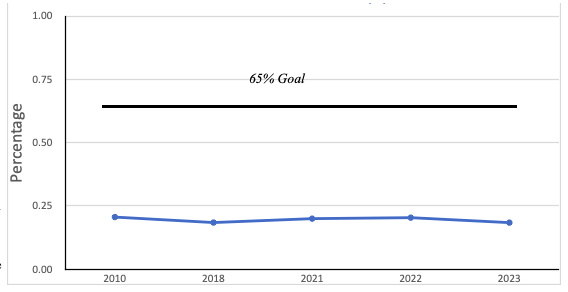

Caribou declines in relation to industrial activity have been observed for many decades, and both B.C. and Alberta acknowledge that conserving and restoring critical caribou habitat is the only way that caribou populations will return to viability. Biologists have even put a number on it: for almost 20 years both provinces have been saying that caribou require a landscape that is about 65 percent undisturbed. The problem is, neither province seems to be moving towards that goal.

Stuck in the past

Alberta has just released a comprehensive report showing that undisturbed habitat has been stuck at about 20 percent for the past 13 years (see graph). A similar report for B.C hasn’t been released yet, but we know the habitat situation there is also not adequate or improving fast enough for caribou to thrive.

These are fairly nuanced concepts which the public can be forgiven for not always staying on top of. Luckily, Phillip Meintzer, a conservation specialist with the Alberta Wildlife Association, has parsed out some of the data from Alberta’s Section 11 Report—essentially a federal-provincial agreement which gives direction on recovery strategy and actions, and staves off an Emergency Protection Order.

Meintzer says that in more than three years, less than one percent of the 209,000 kilometres of legacy seismic lines identified for restoration has actually been restored.

“This means that it would take more than 300 years to restore all of the seismic lines…as long as no new disturbance is permitted,” Meintzer says.

decline because of increased predation. // Mark Bradley

And as for logging, even if tree harvesting stopped today, it would take a very long time for impacted areas to grow back into suitable caribou habitat.

Band Aids

Clearly halting all forestry is too much to ask these governments. But caribou conservation action is mandated by SARA, so if they’re not letting that habitat come back, then the provinces must take other measures. These short term ‘Band-Aid’ solutions to keep caribou from going extinct include:

- Maternity pens: putting pregnant caribou in a pen, and keeping them only until they bear young and their calves are old enough to outrun predators. It’s a nice idea but…it’s difficult to scale up to provide actual population-level recovery.

- Translocations: moving caribou from a hopelessly-small herd to a bigger one. Translocations are pretty much a last-ditch effort, which only save a few individual caribou.

- Supplemental feeding: these programs will increase pregnancy rates, but probably won’t increase population sizes enough, unless you pair it with … (cue ominous drumroll*):

- Predator killing: this is the most severe of the Band-Aid solutions, and it certainly has worked in some cases. However, the rub is that governments have to kill lots of wolves (at least 80 percent), and do it indefinitely (read: forever). Otherwise, the Band-Aid will fall off and stop working. Both provinces have killed thousands of wolves in the name of caribou conservation.

- Culling moose and deer: both provinces also recognize that if you kill a lot of wolves, you’ll end up with more moose and deer… and then eventually even more wolves, once you stop the wolf-killing. As a stop-gap, there have been some measures to encourage hunting of moose and deer.

- Recreation management: for example curtailing helicopter-assisted skiing in sensitive areas. B.C. has done this to some extent, but not consistently, and it is difficult to judge the effectiveness of these efforts. Alberta has promised to manage recreational access to caribou habitat too, but as far as I can tell the government has yet to implement these measures.

The Upshot

So what about those emergency protection orders (EPOs) that the federal government can issue if they feel the province’s efforts are not up to snuff?

Good question. In 2018, the feds looked at the same sort of data I’ve shown you here and, because they didn’t see enough caribou action, threatened Alberta with an EPO if they didn’t smarten up. To avoid that EPO, in 2020 Alberta signed what is known as the aforementioned Section 11 conservation agreement with the feds. As part of that agreement there were supposed to be annual progress reports, but in the five years since they were signed, there have only been a couple of annual reports.

It gets worse. Under the agreement, Alberta was supposed to have already finished what’s known as sub-regional plans, but only two of 11 are complete. The third plan, the Upper Smoky Sub-regional Plan mentioned above, has not been finalized, but has just been released for consultation (you can provide your input here).

Zero stars

And you should provide your input. Because rather than demonstrating progress towards restoration of caribou habitat, the Upper Smoky plan proposes eliminating the current moratoriums on forestry activities and increasing oil and gas activity in the winter ranges of two caribou herds. The proportion of undisturbed caribou habitat—which has been hovering at around 20 percent for more than 10 years—will be reduced, rather than move towards the legally-mandated goal of 65 percent.

Since Alberta seems to be planning to worsen the situation for caribou, it would be pretty silly for the feds to give Alberta a passing grade on caribou conservation when the Section 11 agreement expires this year. We’ll be watching keenly.

Kissing the ring

Alberta seems to be OK with killing predators and coming up with a never-ending supply of recovery plans and agreements – they’re just not great at doing the most important thing: saving and restoring the habitat. There’s a reason for this. In Alberta, the forestry and petrochemical industries employ something like 150,000 people and bring in billions of dollars in government revenue. The government is understandably keen to keep those numbers high.

As far back as 2010, it was estimated that the lost opportunity cost of actually saving Alberta caribou would be on the order of $100 billion. The same study found that while an effective habitat restoration program would run into the hundreds of millions of dollars and take decades, a wolf control program would only cost tens of millions of dollars, and the effects would be almost immediate. You can guess which one they chose.

Cynical cycle

Don’t get me wrong – there are scads of provincial biologists and managers working like Red Bull-chugging beavers to do what they can, and I, for one, truly appreciate their efforts. Roads, seismic lines, and cutblocks are being restored, and hopefully future cutting strategies will be more caribou–friendly (for example big chunks instead of checkerboards, less cutting overall). The caribou situation is certainly better than if they’d done nothing.

But we live in a democratic, capitalistic society. Any politician who announces putting a bunch of people out of work, and at the same time dinging the treasury for millions of dollars, won’t be a politician for long. And in the current climate of tariffs and annexation threats, any mention of the word “environment” has become politically unpopular.

But what does that say about the legacy we are leaving? Are we going to tell our grandkids that rather than restoring habitat, we decided to wipe out wolves and pander to industry? The reality is that caribou are an intractable problem— you simply can’t have resource extraction firing on all cylinders and expect caribou to thrive.

Silver linings

This grim provincial outlook is why large protected areas, like Jasper National Park, are so important for threatened species. National parks represent the last, best chance caribou have for survival. Yes, 36,000 hectares of Jasper was on fire this past summer, and although the fire didn’t burn down core caribou habitat, it certainly won’t be a good thing for caribou if we end up with more wolves in the adjacent habitat where moose, elk, and deer roam.

But there is a lot of unburnt habitat remaining. And we now have a Jasper caribou breeding centre which is aiming to undo the sins of park management past. The idea is to boost caribou density to the point that they can maintain themselves into the future. Right now Jasper caribou are in what’s known as “quasi-extinction”—meaning there just aren’t enough adult females remaining to breed the population out of trouble. And although it’s not quite official news yet (The Jasper Local has learned captures took place six weeks ago, but hasn’t got confirmation from Parks Canada), after decades of studying, hoping, and planning, the facility now houses real, live caribou.

When I was a newly-minted Jasper biologist attending my first Alberta caribou recovery team meeting, one speech by the team leader really hit home. He showed a graph depicting number of caribou research papers over the years — a line going up. He then superimposed the number of caribou — a line going down. The obvious message was that the time for deep thought was over and it was time for action.

That was almost exactly 20 years ago, and I would argue that the required action is still forthcoming. If I were a caribou, I would be pretty steamed about the broken promises and would wonder if Canada should start implementing a reciprocal habitat tariff on industry!

Mark Bradley // info@thejasperlocal.com