Part 2: Home is where the hearth is

In Part 1 of our Walking Through Fire series, we discussed how post-fire vegetation bounces back. But what about animals’ attraction to fire?

There is a small stampede of wild things drawn to fire’s heat and the blackened forests it leaves behind. Some pyro-loving critters find life-giving conditions just after the flames die down, while others rely on post-fire changes in the years to come. One thing that connects them is their adaptations to a home shaped by flames.

Of birds and beetles

My birding friends have been twitching to get a good look at the bird that Cornell University’s bird lab described as “synonymous” with fire. The black-backed woodpeckers appeared after the 2024 Jasper Fire, having located burned trees within weeks of active flames. They came for the bounty of insects drawn to scorched trees. Their dark feathers help them camouflage with the blackened tree trunks, giving fuel to the theory that fire plays a role in shaping species.

Nothing could illustrate this theory better than beetles that evolved into heat-seeking missiles. The wood-boring black fire beetle (Melanophila acuminata) can show up while trees are still smoldering. They detect heat from more than 50 kilometers away, using sensors in pit organs to detect infrared radiation. These sensors give a mechanical energy to their antennae that guides them to fires.

Why are these beetles looking for fire? Burned forests fan the flame of love by allowing them to mate and lay eggs in dead trees. Completely defenseless, dead trees are unable to send sap to “pitch out” invaders. Combine this with little competition from other insects, burned trees become ideal for these beetles to mate and lay eggs. Being possessed to reproduce, they sometime mistake the heat from firefighters’ bodies and give them an amorous (and painful) bite.

One’s loss…another’s gain

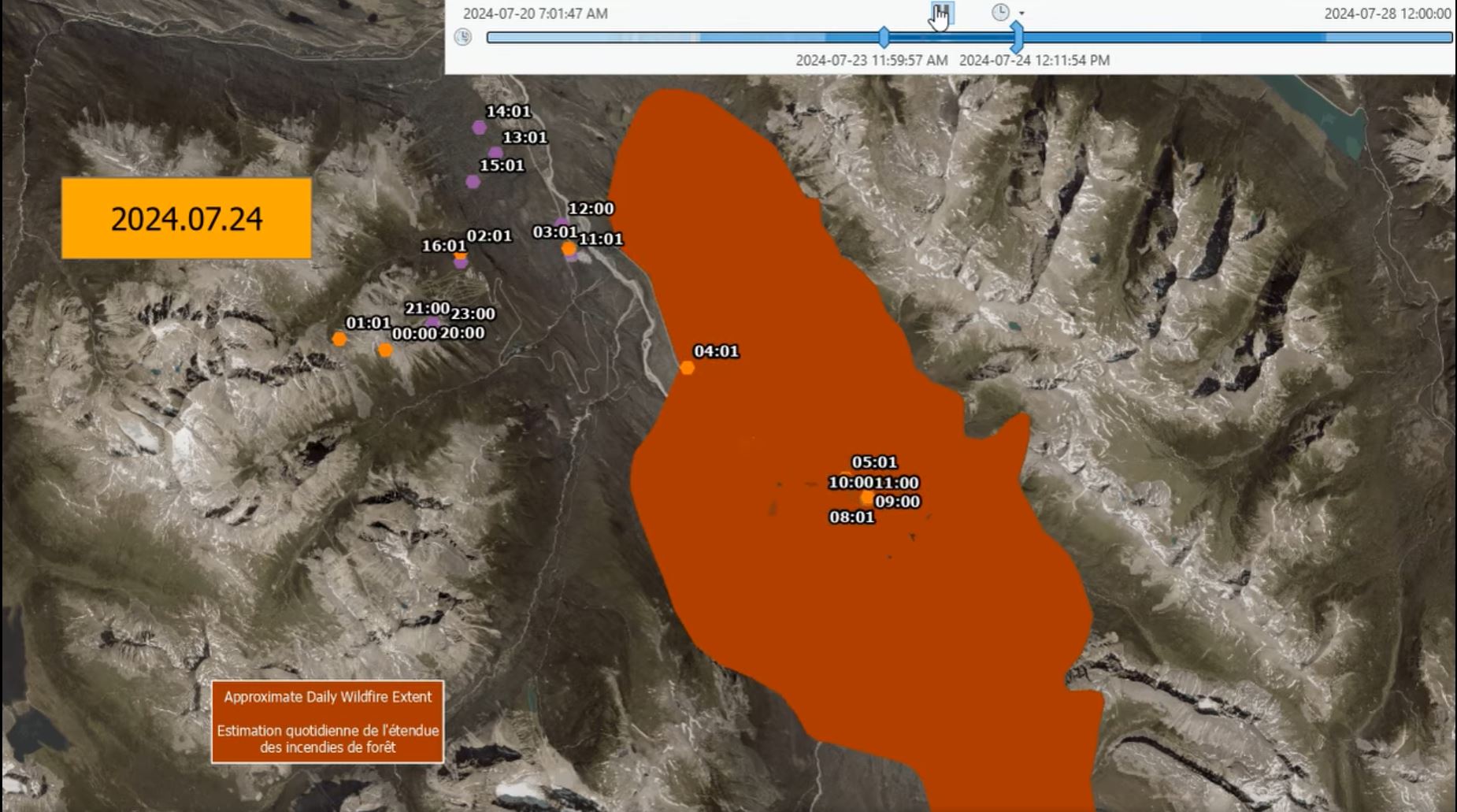

Larger predators also bite into the opportunities fire creates. During the 2024 Jasper Wildfire, Parks Canada was able to track Wolf 262 of the Sunwapta Wolf Pack. Biologists mapped the wolf fleeing the fire, heading up to the Marmot Basin ski area. But, within two days, the collared wolf (and maybe the entire pack) returned to the Wabasso area, where one of the fires originally started. Perhaps the wolves were drawn to the chance to feast on a carcass?

Bears, too, were drawn back behind the fire front; Parks Canada reported seeing grizzly bears feeding on deer and elk carcasses. After the Yellowstone fires of 1988, scientists recorded that 13 of their 21 collared bears had moved back into the burn areas immediately after the fire blazed through. Some were seen feasting on carcasses, while others were rooting through stumps and ant hills, or feeding on newly emerging vegetation.

All bark, no bite

In the winter following the 2024 Jasper Wildfire, I was surprised to see elk and deer where there was no visible vegetation. What were they after? As I walked, I noticed every toppled aspen was being stripped of its greenish white bark. Elk and deer were congregating at these aspen buffets, tearing at the bark with their lower teeth. Weeks later, only the white, bone-like aspen trunks remained. Although I’ve seen living aspens scarred by ungulates, this total bark stripping was new to me. Turns out the bark has a high carbohydrate content and antioxidants! Maybe they were self-medicating while gaining calories?

What will unfold as plants establish themselves in Jasper’s post fire-landscape? Depending upon the severity of the fire, some areas will get a rejuvenation of plants that were struggling due to fire-suppression. Buffalo berry, a crucial food source for bears in the Canadian Rockies, can do well after fire. It may take more than four years for these bushes to start producing good crops for hungry bruins, but there had been many seasons prior to the fire that buffalo berry was in short supply.

Critter litter

Even water-loving critters will see benefits from fire. Decades of fire suppression has been a bummer for beavers and moose. The thick forests that covered much of Jasper prevented willow and aspen from thriving. The open areas created by fires will see a renewal in these plants that are so critical for both species.

The fire might also create new real estate for Columbian ground squirrels. These under-ground dwelling critters need grasslands and open meadows. Decades of fire suppression led to a contiguous carpet of forest, with little open space. Now we might see a boom in ground squirrel populations, which in turn will feed many predators such as birds, bears, and coyotes.

Although the same treeless habitat is not good for red squirrels, their habit of storing cones underground in middens creates a virtual seed bank. After the fire, I walked through the scorched areas of forest and was thrilled to see piles of perfectly preserved cones red squirrels that had brought up from their underground, fire-proof storage areas. Eventually, some of these cone seeds will scatter and return areas to forest, making red squirrels natural property developers.

Wildlife is showing us that sometimes homes are shaped by flame. When we walk through fire, and keep an eye on the living landscape, a story of change and renewal will emerge.

Kirsten Schmitten // info@thejasperlocal.com

About the author:

Kirsten Schmitten is a certified Master Interpretive Guide and a writer who loves All Things Wild.

Want to learn more? Book one of All Things Wild’s guided hikes, talks or step-on guides to find out about Jasper’s natural and historical stories. Call 780-931-6044 or visit allthingswild.ca