May 4 is an auspicious day for Star Wars fans, but it also has special meaning for local bird watchers: it’s approximately when hummingbirds start to arrive in Jasper.

In many ways, hummingbirds are like Jedi Masters. They’re fierce warriors, extremely powerful for their size, and can fly in ways that would make Darth Vader dizzy.

Two birds, one tone

There are only two hummingbird species that live in the Jasper area: rufous and calliope. The calliope, with its throat of brilliant magenta stripes, is the smallest bird in North America. It weighs roughly two grams—the weight of a pop bottle cap—and after the bee hummingbird of Cuba, is the smallest bird in the world. Rufous, which are not much bigger, get their name from their plumage: rufous means “reddish brown in colour.”

A male rufous hummingbird in Jasper. // Mark Bradley

A male calliope Hummingbird. // Mark Bradley

There are 366 species of hummingbirds, and you can find them from Alaska all the way down to the southern tip of South America. That’s it, however; they only live in the Americas. In Africa, Asia and Australia, the ecological role (or niche) of hummingbirds is occupied by sunbirds. Sunbirds are similar to hummers, but they are larger, and because they lack the ability to hover, they must feed from perches.

The aptly named Scarlet-chested Sunbird in South Africa. // Mark Bradley

Advertising inquiries: andrea@ravencommunitymedia.com

Size matters not

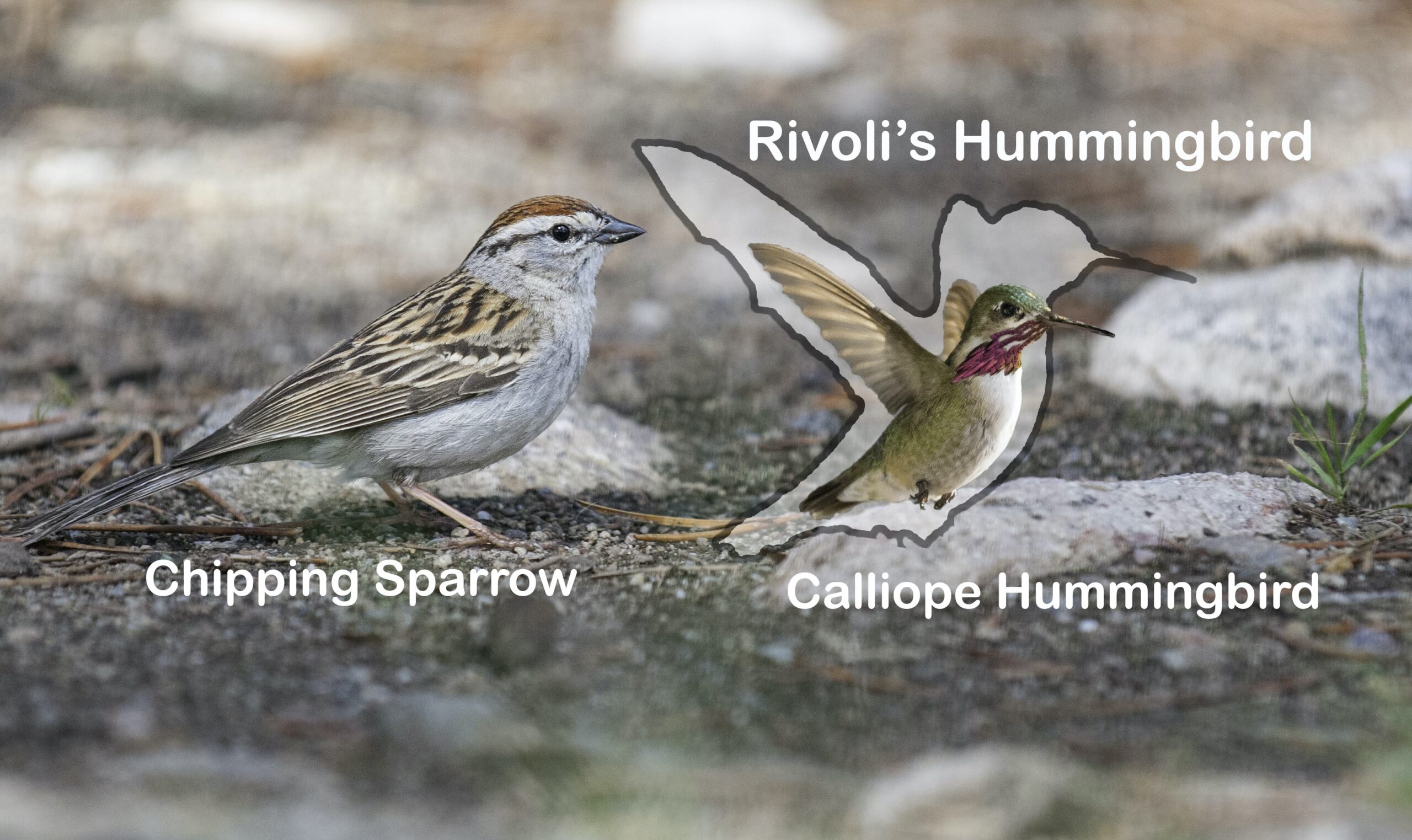

Hummers come in a bewildering assortment of colours, and while they conform to the same basic body plan, some are much larger than others. This was demonstrated to me while doing field work in Arizona. It was a hot afternoon, I was peering intently through a spotting scope and I could feel rivulets of sweat running down my back. My assigned tasks were to monitor a nest of bushtits (tiny songbirds), and to record banding information of any other birds that showed up. Suddenly, what sounded like a lightsaber buzzed near my ear and I felt something alight on my shoulder. To my astonishment, it was a (relatively) huge Rivoli’s hummingbird—not quite the size of an Ewok, but at least two times the size of either of Jasper’s hummingbirds, and with a wingspan of seven inches, about the same size as one of our chipping sparrows.

Comparative sizes of a Chipping Sparrow, a calliope hummingbird and the outline of a Rivoli’s hummingbird.// Mark Bradley

Balance to the force

Like Yoda with his root-leaf stew, hummingbirds stick to the same basic diet: flower nectar. They will occasionally catch small flying insects, especially when they are feeding their young, but for the most part, it’s all about the nectar. To get at that sugar-rich liquid, evolution has given hummingbirds a unique superpower: the ability to hover. This is where they play their Jedi mind tricks on observers: they are the only bird known to fly backwards for any length of time. Hummingbirds are able to perform this aerial manoeuvre because of a special adaptation. While most birds’ wings flap up and down, with the power coming from the down stroke, hummingbirds’ wings rotate laterally, in a figure-8 pattern. The power—heck let’s call it the force—comes from both directions.

Hummingbirds’ unique stroke is enabled by a unique ball and socket joint which attaches their wings to their shoulders. Hummers also have very large flight muscles for their size—both in front of, and behind, their shoulder joint (most birds only have large muscles for powering the down stroke). Hummingbird wings can beat as fast as 200 beats per second, so their wing bones are shorter and stubbier than most other birds. When a hovering hummer’s wings go into warp speed, most of the blur you see is feathers.

Jedi juice

All that hovering at 200 beats/second takes energy, and lots of it. One of the reasons people love hummingbirds is that they will readily accept the energy we supply them, in the form of sugar water. If you are going to put a feeder out, a mainly-red one will attract them. Don’t, however, use red dye in the nectar—it’s unnecessary and may well be harmful. The nectar should be four parts water to one part white sugar. There’s no need to boil the water, but you should clean your feeder once per week, to prevent mould. If you want more than one hummingbird at a time, you’ll need several feeders—they jealously guard their feeders. And beware an attack of the clones—wasps will go after the nectar like Tie Fighters on an X-wing. Some feeders come with guards to keep wasps out. Biggs Darklighter could only be so lucky.

A male rufous hummingbird partakes of some sugar water.

Jedi jewelry

Besides their minute size and powerful wingstroke, the first thing that many people notice about hummingbirds is their shiny, colourful throats. The area is known as the gorget. Paradoxically, a hummingbird’s gorget contains only black pigment. The reason a rufous hummingbird’s gorget, for example, appears to be Darth Maul red is because the microstructures in the bird’s feathers reflect red light. But they only do it in one direction. When the light is coming from the other way, a rufous’ gorget appears to be Darth Vader black.

A male rufous hummingbird, showing off his luminous gorget. // Mark Bradley

The same bird, but now his gorget is not reflecting the light. // Mark Bradley

Because of those spectacular gorgets (as well as body colour), it is pretty easy to tell a male rufous from a calliope. The females and juveniles are harder to identify—they lack these colourful gorgets—and size can be confusing if you only see one of them. To be sure, it’s best to catch them when they are perched on a twig. The rufous’ wings don’t quite reach the end of the tail, while the Calliope’s wings come just about flush.

A juvenile rufous hummingbird. Wings stop short of the tail. // Mark Bradley

From Padawans to pilots

Luke Skywalker had to go to Dagobah for training, and hummingbirds, too, before they can become fully-fledged Jedis, must go through their egg and nestling phases. Nests are built in trees from small twigs, decorated with lichen and moss, and glued together with the silk from spider webs. The eggs are teensy—only a half inch across and weighing about half a gram, a little smaller than a jellybean. There are usually two or three eggs, and they hatch in about two weeks. Only three weeks after that, the chicks fly away. In barely more than a month, hummingbirds go from a freshly laid egg to a full-sized hummingbird! Talk about hyperdrive!

A pair of rufous hummingbird chicks. One is practising its figure 8 wing beat. // Mark Bradley

Most birds, when they leave the nest, sort of flap and glide awkwardly for a few feet, before crash-landing somewhere below their nest. Hummingbirds however, cannot glide—those little wings simply don’t have the surface area for it. I remember watching a hummingbird chick leave the nest for the first time. For a long time it practised beating its wings. It sat on the edge of the nest, frantically whipping them back and forth, buzzing loudly. Then, finally, it flew—but not down. It zoomed straight up into the spruce tree and disappeared into the foliage! Anakin Skywalker would have approved.

Advertising inquiries: andrea@ravencommunitymedia.com

The Force is strong in this one

Despite their diminutive stature, hummingbirds are among the most aggressive pilots in the avian world (let’s say galaxy). They are constantly fighting, chasing competitors away from valuable food sources, whether flowers in nature or feeders in our backyards. Male rufous hummingbirds’ air shows also include what biologists call “J” and “shuttle” flights—both of which are meant to impress females. The J flight pattern starts up to 50 feet in the air, then dives straight down, pulling up just above the ground to form the “J.” Air rushing through their tail feathers at the bottom of the J makes a chittering, buzzing sound. The shuttle flight is less dramatic—the hummers zip back and forth, in front of a perched female. But because of where this delicate dance takes place—only a foot or two off the ground—the Jedis-in-training often fall prey to neighbourhood bounty hunters, otherwise known as cats.

A juvenile Calliope Hummingbird. Wings are the same length as the tail. // Mark Bradley

May 4 is auspicious date for Star Wars fans, but for Jasper birders it’s a day that marks the Return of the Jedis. The next time you see a hummingbird, judge them not by their size. Size matters not, for the Force is strong with these ones.

Mark Bradley // thejasperlocal@gmail.com