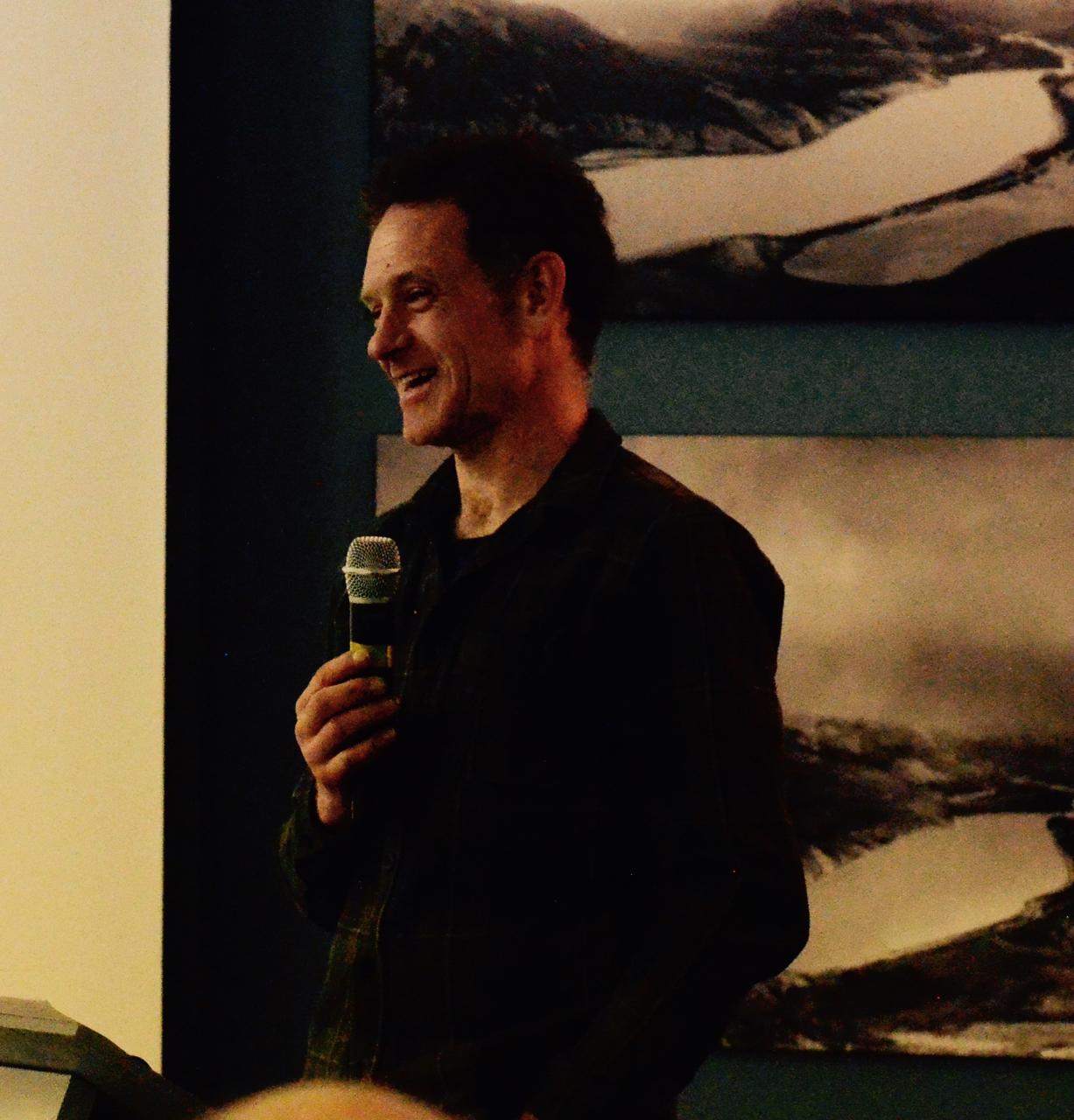

Jasper roping up for celebrations of Mount Alberta’s 1925 inaugural ascent

If you are going to steal a mountain in Jasper, I’d recommend Mount Alberta.

It’s old (around 75 million years), but lightly used. It’s almost completely hidden from the Icefields Parkway—crowded in among more popular peaks—so it shouldn’t be missed. It’s pretty big, maybe tough to fit in your hatchback, but if you believe our premier, its name alone makes it invisible to the rest of Canada. If you want to steal a mountain from Jasper, Mount Alberta’s your berg.

In 1925, stealing a mountain was less on the mind of Yuko Maki than stealing a moment in history. The experienced mountaineer and senior member of the Japanese Alpine Club (JAC) was leaning on the front rail of a steamer in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, destination: Seattle.

With the backing of the Marquis Mori Tatsu Hosokawa, member of the Japanese royal family, and sponsorships from two Tokyo newspapers, Mr. Maki was perhaps also focussed on stealing a headline. And why not? His goal was to lead a Japanese climbing team up one of the tallest and most difficult peaks in the Canadian Rockies yet to be summited. This would be a seminal event not just for the JAC, but for the mountaineering world.

Mr. Maki’s adventure started as so many do—with a touch of serendipity. As described in Chic Scott’s 2000 chronicle, Pushing the Limits: The story of Canadian Mountaineering, Mr. Maki was guiding Prince Chichibu (brother of the future Emperor Hirohito) in northern Japan when the royal handed Mr. Maki a book: A Climber’s Guide to the Rocky Mountains of Canada, by J. Monroe Thorington. Pointing to the book’s cover, the prince suggested that this be Mr. Maki’s next destination. As if by royal decree, Mount Alberta became Yuko Maki’s calling.

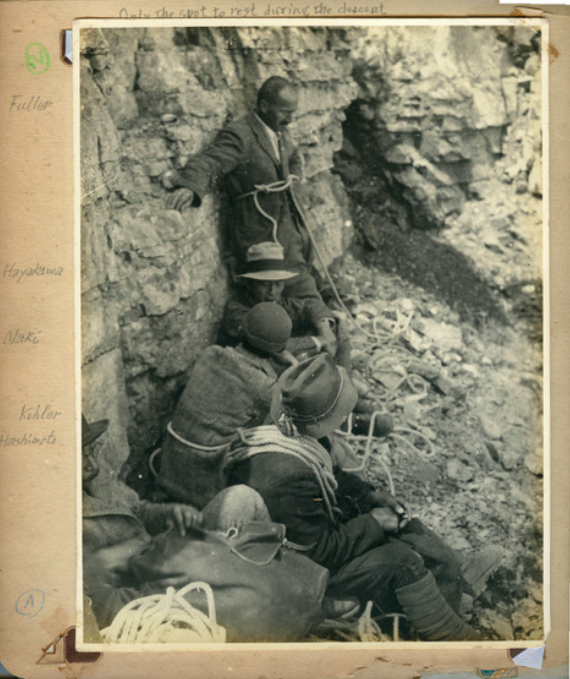

One hundred years later, one can imagine the excitement and nervousness in the Japanese crew as the port of Seattle breached the eastern horizon. Fully aware of the historical significance of the trip and with the pressure from his royal supporters, Mr. Maki had assembled an expedition team that was more of a Swiss Army Knife than a Samurai katana. Drawn from the ranks of Japan’s skiing community, Mr. Maki enlisted H. Hatano, a geologist, geographer and horseman; Y. Mita, a botanist and artist; T. Hayakawa, a doctor; S. Hashimoto, translator; and N. Okabe, a photographer, to fill his team. From Seattle, they boarded a train to Canada, arriving in Jasper in June, 1925.

The echoes of their arrival reverberate in Jasper even today. The train station that greeted them, the building that still dominates Jasper’s centre, was still under construction. The original structure burned to the ground the winter before. Jasper Park Lodge, where they were based to prepare for the climb, was pulsating with activity from crews completing the just-opened Jasper Park Golf Course. There was smoke in the air from wildfires raging to the south of town in the area of Sunwapta Falls, and fire crews from all over western Canada were staging in Jasper. The chaotic setting of Jasper National Park in 1925 was a far cry from the comfortable order of Imperial Japan they had left a month before. But their adventure was just beginning.

Whether their first meeting with their hired Swiss guides was a reassuring or intimidating encounter is a story untold. Heinrich Fuhrer and Hans Kohler were both experienced alpinists and, at the time, working for Canadian National Railway as part of a service to entice tourists to the Rockies. From the account of Jean Weber, a young Swiss “adventurer” hired by Mr. Fuhrer to also accompany the expedition, the guides were both wary of the mountaineering inexperience of most of the six-man Japanese crew, and surprised by the diminutive stature of the group’s leader, Mr. Maki. However, Mr. Maki was comfortable with the ways of Swiss Guides, having been on a team that was the first to climb the Mittellegi Ridge route on The Eiger, Switzerland, four years earlier.

Confident in his, and his team’s, abilities, Mr. Maki was undaunted in preparations, and by the end of June they were on the trail down the Athabasca River Valley towards their objective.

Mount Alberta is not a peak familiar to many residents or visitors to Jasper. Unlike Mount Edith Cavell or Pyramid Mountain, it is not frequently climbed and, for about 100 years, there have only been a few places where it could be seen from Jasper—or even the Icefields Parkway. However, as has become clear to everyone in these parts, last summer’s wildfire has dramatically changed the local viewscape. Guided by Greg Horne, local adventurer, historian, and raconteur, I learned that Mount Alberta is now clearly visible from town in several places. I can’t take my eyes off its snowy summit these days—looking south from the intersection of Pine and Connaught, it’s just off the descending western ridge of Mount Kerkeslin. In plain view, Mount Alberta will be significantly more difficult to steal these days.

Mount Alberta is known among the climbing community as a massive pile of rubble. Just ask Jasperite Dana Ruddy who has climbed it twice—once in a single day. Or Steve Roper and Allen Steck, authors of Fifty Classic Climbs in North America, who called Mount Alberta one of the Rockies’ most “notorious” peaks.

Along with being difficult to climb, in 1925, the mountain was not easy to get to. Tucked in between Mount Woolley and the upper Athabasca River in the Winston Churchill Range, Alberta tops out at 3,619 meters elevation. According to Warren Waxer, who helped organize the ceremony honouring the 75th anniversary of Mount Alberta’s first ascent, then-Premier Ralph Klein asked why anyone in their right mind would want to climb a mountain you can’t even see from the highway?

Mr. Maki and his intrepid crew must have been asking themselves the same question in 1925, 15 years before the Icefields Parkway was constructed. Their route took them through recently-burned forests, trees still smoldering, and fire crew camps. Advice they had received from an American team led by Val Flynn—who were turned away from their Mount Alberta ambitions by the forest fires—was enough to get Mr. Maki and his entourage to the base of Mount Alberta, on the banks of Habel Creek, by mid-July. In the early morning of July, 20, 1925, the crew of nine climbers were finally ready to climb.

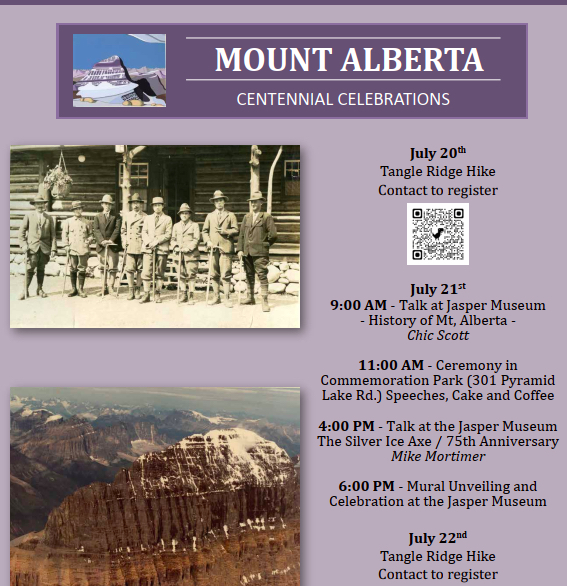

If you want to find out what happened next, I encourage you to take in the events happening in Jasper between July 20 and 22 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of this first ascent. There will be hikes, speeches, cake, and a new mural—all unveiled at the Jasper Museum (400 Bonhomme Street).

There will even be another attempt on the summit by a youthful contingent from the JAC. Senior members of the JAC will grace Jasper with their presence, as will the Consul General of Japan in Alberta, Mr. Wajima Takehiko. Prominent members of Jasper’s alpinist community will also be there to answer the many questions that you must still have.

John Wilmshurst // info@thejasperlocal.com