A rare ascent of a local peak, a climber campaigning to honour his family, and an uncovered register of heralded names in Jasper National Park’s alpinist community.

The ingredients of a mountain tale, if there ever were any.

For the past two summers, 31-year-old Andrew Everett has hung his helmet near the toe of the Athabasca Glacier. During the day, he drives ice explorers for Pursuit. Most nights, from the window in his staff dorm, he has eyed, with a climber’s curiosity, the pointed spire next to prominent Nigel Peak.

“I see the mountain every day, I felt drawn to it,” Everett said.

Through his rudimentary research about the mountain, he discovered it is known as Nigel 2, or Nigel SW3. Local monikers, but no official name. Everett thought that odd.

“It’s not a satallite peak, and it sits on the boundary between Jasper and Banff National Parks. It defintely deserves a name,” he said.

Everett also couldn’t find any definitive answers of whether anyone had been to the peak’s summit.

“No one around here had known anyone to have done it.”

Which of course made the idea of climbing it—and perhaps even naming it—all the more alluring.

Everett—a keen adventurer who learned to rock climb with his father on the crags near his North Yorkshire, England, home—thus hatched a plan. He would recruit a small reconnaisance party, and, depending on what they found, return to the peak at a later date with the appropriate equipment, strategy and ambition.

Their June 6 recon mission ascertained what many mountaineers find in the Columbia Icefields Area: the climbing isn’t that hard, but the rock is absolutely shite.

When he and his mates came back on June 28, Everett headed for the summit alone. His friends watched as he navigated the crux—only an eight metre pitch, but one comprised of loose, crumbly rock, and perched hundreds of metres in the air.

“Terrible rock was just pinging off everywhere,” Everett recalled.

As he reached the top of the pitch, with sheer drops on either side of him, Everett spied something foriegn in the alpine environment. It was a metal piton—a climber’s tool, for a climber’s rope. Knowing his ascent of the 3,000 metre spire was clearly not the first, he was somewhat deflated.

“I was kind of bummed, to be honest,” he laughed.

But he couldn’t hang his head for too long—he still had a short, but exposed, scramble to contend with.

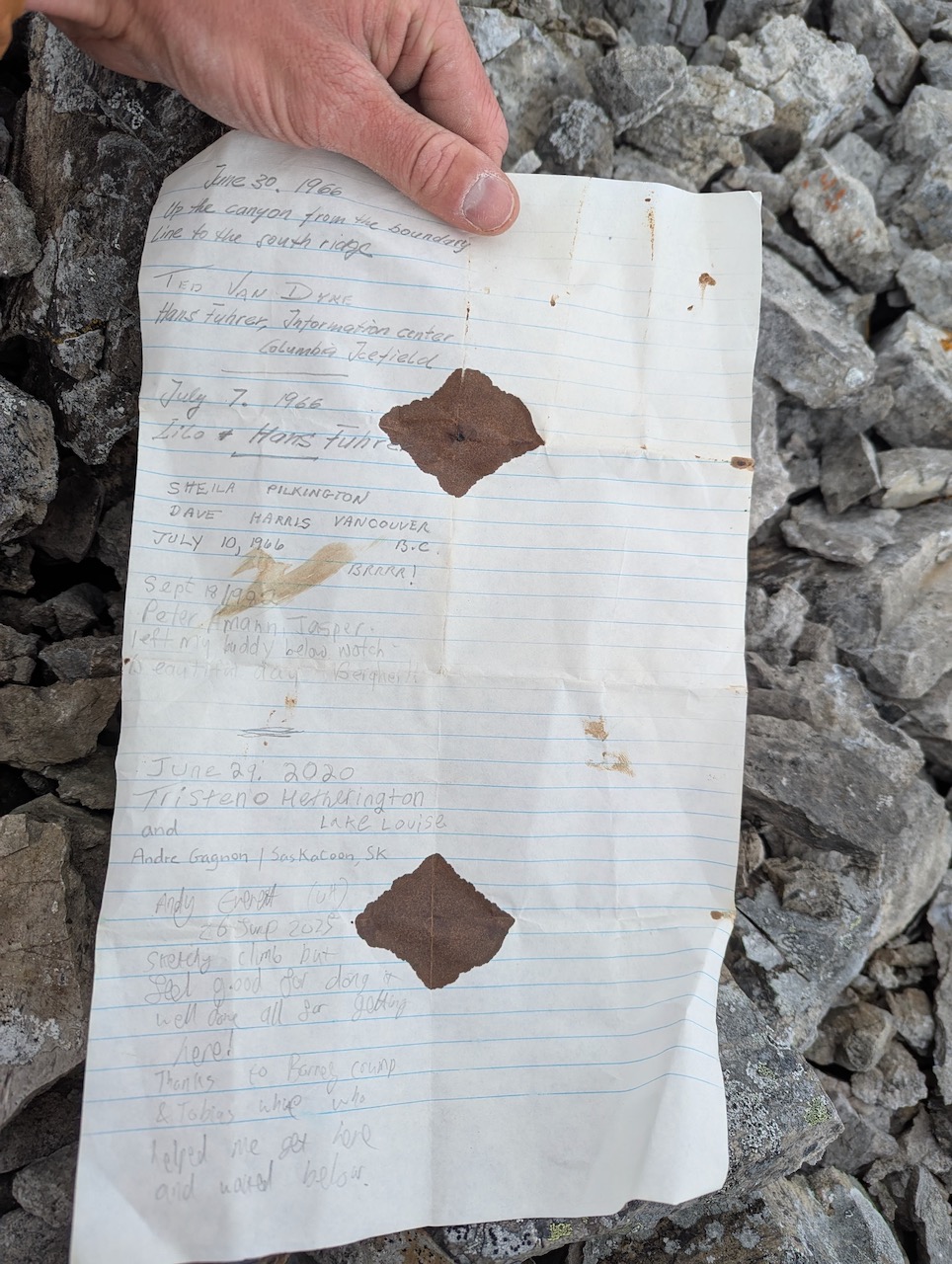

When he reached the summit, Everett’s spirits lited. In the small cairn he found sat a glass jar. Within the jar was a “great treasure”—a summit registry, containing the names of those who’d been there before him.

As he unfurled the yellowed paper, Everett discovered at least five parties had been atop this brittle peak: the register showed that in 1966, a party led by Hans Fuhrer, the pioneering Swiss ski instructor who worked in various roles for the national parks service; the next in the registry was Fuhrer again, this time with his wife, Lilo, only a week later; there was another party in July, 1966 (perhaps Fuhrer encouraged them from his post at the Columbia Icefields office); the eminent Jasper mountain guide, Peter Amann, was there in September 1982; and Bow Valley photographer and musician Tristan O’Hetherington made a COVID climb in June of 2020.

While Everett wasn’t aware that he had shared the summit space with several prominent Jasper alpinists, he was chuffed, all the same, to know that others, like him, were drawn to the peak.

“I was delighted to see this piece of history and see the legacy of those who had made it that far before,” he said.

Amann, who moved from Jasper to Tete Jaune, B.C., had more insights into the N2’s peakbagging history: he reported that the first party was actually in 1937, as he had discovered a deteriorating piece of paper in a rusted can on the summit when he first climbed it in.

“The first ascent party called it Tenacity Peak,” Amann recalled. “Pretty cool [for Everett] to get the consolation prize of a fine summit register.”

The only thing missing on the mountain, Everett believes, is a proper name. Which is why he is submitting to Natural Resources Canada that the peak be called Mount Dave Lorainne, in honour of his parents.

“My dad taught me how to be a mountaineer and my mom raised me,” he suggested.

Submitting a placename in Alberta begins with the submission of a proposal to the Alberta Geographic Naming Program.

When submitting for a geographic feature within a national park, the process becomes even more extensive, requiring decisions from the Alberta government, Geographical Names Board of Canada (GNBC) and Parks Canada.

After consultation with Indigenous communities and the local population, and verification that the name complies with the principles of georgraphical names, a decision can take several years.

Everett acknowledged that his proposed name doesn’t comply with some of the naming principles—such as that commemorative names will not be approved for people still alive—but he still plans to submit the proposal.

“Even if they give it any name, I’d be quite happy,” he said.

Regardless of the outcome of the proposal, Mount Dave Lorainne will likely stick—to Everett and his colleagues at the Columbia Icefields Area, at the very least.

Bob Covey // bob@thejasperlocal.com

-with files from the Local Journalism Initiative