A father and son’s five-year journey to summit mighty Mount Robson

From a distance, Mount Robson looks like something painted onto the horizon.

Its glaciated ridges and sheer cliffs dwarf everything around it. At 3,954 metres, the ‘King’ of the Canadian Rockies commands not just admiration, but respect.

Climbers know it as one of North America’s ultimate summits, with claims that just one in 10 attempts are completed successfully. For most, it’s a view to marvel at. For Montreal father and son, Steve and Alec Sinki, however, surmounting this colossus was half-a-decade in the making.

The seed of this idea took root in 2020, during a cross-country family road trip. Driving through the craggy heart of British Columbia, suddenly through the RV windshield Robson emerged — a jagged giant, its head wrapped in clouds. Steve pointed it out, calling Robson the ‘most beautiful mountain in the Rockies.’ He half-joked to Alec that if he ever had a son of his own, he should name the child Robson. The gag turned into a fascination, and by the time they were back in Montreal, they were already planning their climb attempt.

Mount Robson has long pulled people toward it. Nicknamed Yexyexéscen or “striped rock” by the Shuswap custodians of the land on which the mountain sits, the first documented successful summit was in 1913. Austrian guide Conrad Kain, alongside William Foster and Albert McCarthy, reached the peak via what would later be known as the Kain Face — a steep, 800-metre wall of ice and snow. A few years prior to Conrad Kain and his team, Reverend George Kinney, a founding member of the Alpine Club of Canada, claimed he reached Mt Robson’s peak in 1909, but his story was met with doubt, and debate still lingers over whether he actually reached the top.

And, over the more-than-one-hundred years since then, Robson’s history has been written by legendary ascents, tragic disappearances, and ambitious routes like “Infinite Patience” on the Emperor Face—a 2,200-metre vertical climb that only the boldest and best climbers in the world attempt.

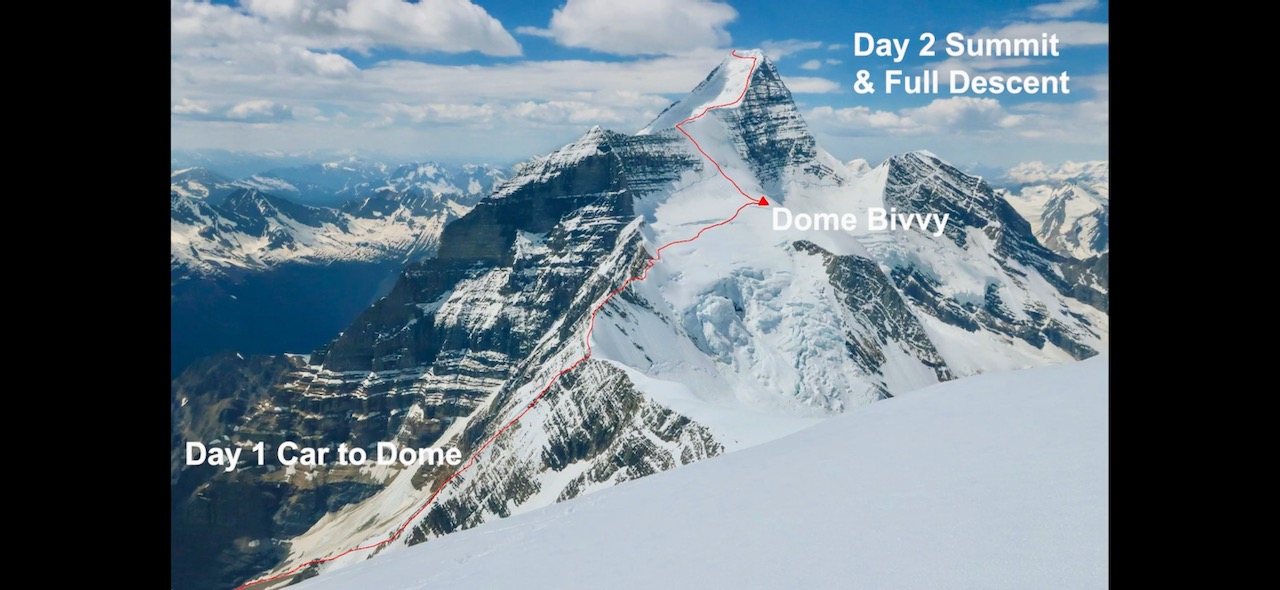

Steve and Alec chose to route their journey in the icy footsteps of Conrad Kain, up Kain Face—a mix of glacier travel, ice climbing, rock scrambling, and exposed ridge work.

In 2023, they set out for their inaugural attempt, the adventure doubling as a birthday commemoration for Alec, who had just turned 18. They and two of Alec’s friends began the ordeal, and the team made good progress until disaster struck: injury to one of the younger climbers, at a trecherous point in the route known as ‘the spires.’

Knowing they were now in a more challenging scenario than they had prepared for, the party turned back.

A year later, for Steve’s 50th birthday, the Montral-based duo tried again. This time, the mountain threw wet weather at them. They fought their way to the same jagged spires, but again had to retreat when Steve’s boot began to peel off.

Tied together on a precipice where one slip could drag both men down into an icy void, Steve and Alec knew there was no easy solution for a moment such as this. With heavy hearts they made the decision to turn back. But they were determined, again, to return.

“It was a 2,000 metre trip down the mountain with a broken boot that we had to tie, wrap, tape and do all sorts of things to in order to keep it together,” Steve recalled.

Mount Robson is not a peak that rewards persistence without preparation. Like most alpine regions, storms can roll in with little warning, turning a clear day into a complete whiteout. Robson’s slopes are riddled with crevasses, icefall zones, and avalanche hazards. In many ways, the experience is akin to a game of Russian roulette with the mountain — one wrong move, misplaced hand or misstep can spell your life’s end, and potentially that of your partner as well.

Knowing this, in summer 2025, Steve and Alec set out for their third attempt.

“In French we have an expression: ‘Jamais deux sans trois—never two without three,” so we said the third attempt has to be the right one.”

They travelled light — just 40 pounds in each pack, with gear stripped to the bare necessities. Food, fuel and water were calculated exactly, leaving completely zero margin for error or delay.

“Every step mattered,” Steve said. “You couldn’t let your focus drift for a second.”

That intensity is something Steve thrives on. He compares it to the precision of a surgeon—every movement deliberate. The difference, of course, is that Steve and Alec’s operating theatre is a knife-edge ridge with an unforgiving 3,000-metre plummet to Berg Lake on one side.

Complicating their progress were Steve’s boots. They stayed together this time, but they were too tight. His big toe was bearing the brunt of each step. The nail was falling off.

“Every step was really, really, really painful,” he laughed, in hindsight at the memory of the pain. “And you know, when you’re smashing your ice crampons repeatedly into a solid wall of ice it really, really hurts.”

However, they had come too far to be held back by such an obstacle.

“I’m not going to let the expedition go bad because of that,” he recalled stoically. “I also lost one of my rappel devices, so that was another challenge when we had to use the rope.”

Despite the seriousness of the task at hand, humour found its way in. Steve recalled one morning being perched on a slope, attending to ‘personal’ business, when his toilet paper roll slipped away and snowballed down the mountain.

“I had to yell across the glacier for Alec to bring me more,” he laughed. “These are the real challenges no one talks about!”

There were other moments that pushed them to their limits: On the Kain Face ice wall, Steve lost his crampon.

“I shouted to Alec to stop carefully,” he recalled.

He got it back on. But Steve knew that on an ice wall, tied together, one slip could have very easily sent them both sliding down the mountain.

Most pitches, 20-year-old Alec was leading. They needed his confidence and energy up front. And letting Alec take the lead meant Steve had to trust not just his skill, but his judgment.

Still, at various moments of meditative, conscious movements, Steve said he felt the weight of fatherhood much more than the weight of his backpack.

“I’m constantly thinking that if anything goes wrong and he doesn’t come back home with me, there’s no way I could live with that.”

“But the way I see it: If you want to see the best of what earth has to offer— of what God gave us—there’s great risk. And with great risk comes great achievements.”

In Quebec, the Sinkis are keen ice climbers. Their mountaineering training has been a mix of rock climbing, ice climbing, alpinism, winter camping and glacier travel. They practice crevice rescues, take avalanche safety courses and simulate hazard mitigation.

Over the years of preparation for this expedition, Steve and Alec learned to move together like a well-oiled machine. As such, it was during these times—like when quietly, efficiently setting up camp on the glacier, one pitching the tent, the other melting snow for water— that they truly cherished the experience.

“Those are moments that I remember because we really needed each other. Those are the moments that are very personal,” Steve said.

Crossing a torrent of glacial water at the base of the mountain was another one of those seemingly small but unforgettable moments — arm-in-arm, each helping the other over slick, unstable rocks, knowing that one misstep could sweep their packs and hopes down the river.

Steve added that the most mentally gruelling moments happen when you think your energy is completely depleted.

“When you feel you’ve hit zero, there’s always another 20 percent in the tank,” he says.

“You just have to dig for it.”

That spirit carried them through exhausting days that began at 3 a.m. and ended at 9 p.m., with hours spent moving over dangerous terrain, where rest wasn’t an option.

When they reached the final push to the summit, the air was thin and the world below seemed impossibly far away. Steve was belaying, taking in rope as Alec climbed the last dozen metres.

“I think I had tears in my eyes. Just seeing him come up and we’re roped together, bringing a rope to me and he’s at the other end of it—that’s the number-one highlight.”

They didn’t linger long. On Robson, the summit is merely the halfway point — the descent off the mountain can be even more dangerous than the climb. But for those few minutes, the two men let the view and the moment wash over them.

The mountain stretched out in all directions—the Columbia Icefield shimmering to the south, the wild expanse of Mount Robson Provincial Park to the north. Far below, the waters of Berg Lake glimmered like turquoise glass.

The duo’s climb up the Kain Face of the striped rock Yexyexéscen puts Steve and Alec in the company of a select group of climbers. Over the years, storms, accidents, and the mountain’s steep degree of difficulty have kept nine out of 10 mountaineers from reaching the top. Some have never returned.

For this father and son team, the rope they shared on their Robson climb signified far more than just their safe travels on the mountain. For Steve and Alec it carried three years of preparation, two retreats, laughter, frustration and fear. It tethered them across rivers, over glaciers, and into the thin air where the horizon rolls on forever.

Their story builds on a life-long father-son bond — a shared experience of persistence, trust in each other, and the tears of pure joy when the stakes are thousands of metres high.

Cameron Jackson // info@thejasperlocal.com

Cameron (CJ) Jackson is a media specialist working for the Canadian Red Cross in Jasper, AB.