Stocked fish poisoned to protect native trout in Banff’s high alpine

From the August 15, 2021 Jasper Local

Hunkered down on a flat rock high above Dolomite Pass in Banff National Park, I dig through my pack and locate my cheap pair of Bushnells.

Chomping a sandwich and glassing the surrounding mountains, I see scramblers making their way up nearby Cirque Peak. A group of backpackers tramp through the meadows, their hiking poles clicking on the trail. Somewhere in the rubble below me, picas sound their urgent alarms and overhead, clouds are piling up. Just when the cumuli threaten to darken, however, the clouds move on, allowing scattershot beams of sunlight to burn through and highlight my destination, 500 metres or so down a glacier-scraped slope.

Long and narrow, nestled beneath the rugged crags of Dolomite Peak, I’ve been dreaming about Katherine Lake since last week, when I hastily cobbled together plans to visit the area with a group of people I’d never met before. The internet’s fickleness didn’t disappoint, for despite the grand ambitions of those showing interest in coming along, I am by myself today. That’s ok. As I scan the shoreline intently, I soon find what I’m after. Few things are more promising to a person alone in the backcountry with a fishing rod than the tell-tale rings of fish rising. The sun glints off the expanding ripples and I wink back. Shouldering my pack, I practically sprint to the lake.

Last summer, I could have gone through a similar routine while peering down at this popular trail’s namesake. If there were insects hatching or being blown onto the surface of Helen Lake, surely I could have spotted the odd rise of an Eastern Brook Trout, a red and green-speckled non-native sportfish beloved by anglers over for its beauty, fighting strength and willingness to take a lure or fly.

This year, however, Helen Lake is devoid of rise ripples. In August of 2020, Parks Canada biologists used a fish-specific toxicant called rotenone to rid Helen Lake of brook trout, an effort to reverse the now-out-of-vogue fish stocking programs of decades past and subsequently reintroduce genetically-pure, native species to connecting streams. Some anglers call the fish kill blasphemy, a righteous and exorbitant initiative that deprives anglers of an experience that helps foster national park stewardship. BNP aquatics specialist Shelley Humphries, on the other hand, calls it restoration.

“Westslope cutthroat are probably occupying less than 10 per cent of their historic distribution,” Humphries said in an interview with The Jasper Local last year.

Hybridization with introduced fish, along with being outcompeted, has depleted the westslope gene pool. For the most part, stocked rainbow trout are doing the hybridizing in the Bow River drainage but there’s another culprit that, after seven decades of spawning in Canada’s mountain parks, has mixed with the natives: the Yellowstone cutthroat.

Yellowstone cutthroat are prized as gamefish. Because they feed primarily on insects as adults (unlike brown trout, for example, which are more piscivorous), they are particularly sporting for fly anglers. And as I had just witnessed through my binoculars, Katherine Lake was full of them.

As I stare intently at my casted-out fly, its yellow fibres barely discernible in the glare of the midday sun, I raise more than a couple eyebrows among the Gortex-clad family hiking out of the Dolomite Valley. Soon enough, however, the presentation is raising the interest of an even more colourful character; the dark snout of a cutthroat pierces the surface of the water. In my excitement I strike too early and miss the take. A curse word echoes around the natural amphitheatre and I see the pre-teen hiker heading up the boot-beaten path crane his neck in wonder. Had he stuck around, he might have seen the next fish stick to my tiny hook. No matter, it’s just myself and the cutties today. Normally if I have the honour of landing such a special fish in such a special place I’d go through a ritual of thanks before releasing it back to its aqueous home. Since Parks Canada staff will be here tomorrow with their rotenone, however, I use my hiking pole to bonk the 16-inch trout between the eyes.

“It’s either today or tomorrow, fella,” I mumble before wrapping it in wet grass.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that Parks Canada began to look at trout habitat through a naturalist lens and the fulsome stocking programs of the past became passé. Fish hatcheries in Banff, Jasper and Waterton were decommissioned as the agency wanted to leave waterbodies in their natural state. The problem, of course, was that the damage had been done. Brook trout in particular didn’t get the memo that policy change was afoot.

“[Park managers] were definitely trying to leave space for native fish but by the time they made that decision it was kind of too late for some of them,” Humphries said.

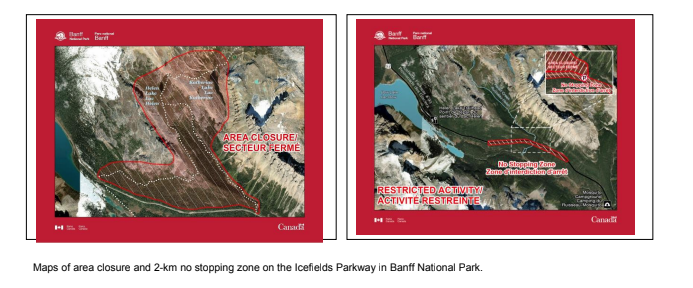

Fifty years or so later, depending on your point of view, those wrongs are being righted. On August 9, the day after I landed seven magnificent Yellowstone cutthroat and lost a half dozen more in one of the most spectacular valleys I’ve ever had the pleasure of casting a fly, aquatics specialists were dripping rotenone into Katherine Lake. Rotenone, a toxicant that originates from a tropical bean plant and which indigenous people from French Guiana have traditionally used to harvest fish, doesn’t affect mammals or birds and because its active compound is broken down by sunlight, water and turbulence, it does not remain in the water. Still, to facilitate the restoration operation, Parks Canada closed the Helen Lake/Dolomite Pass area to the public for nearly two weeks, enforcing a no-stopping zone at the trailhead and warning that anyone contravening these measures could be hit with a $25,000 fine.

If that seems severe, Parks Canada has said it takes its mandate to protect and restore ecological integrity very seriously. The no-stopping zone is in place to ensure road safety around waters that are being neutralized, the agency said in a press release. Park users familiar with the rotenone process will know that as a result of the neutralizing agent, the affected waters temporarily turn pink—a tourist jam waiting to happen if there ever was one.

As an angler, knowing that Katherine Lake’s Yellowstone cuts are a thing of the past is disheartening, to be sure. I can think of few better ways to introduce my young kids to the richness of the outdoors than by casting to willing fish surrounded by protected wilderness. But then I think of the issues faced by the westslope cutthroat, a species that survived over millennia only to be persecuted to near-extinction in the last 100 years (their current status in Alberta is threatened) by habitat destruction, over-harvesting and mishandling, and I know there’s…(ahem) bigger fish to fry.

Alberta is home to some of the most abundant trout angling opportunities in the world. We can spend a lifetime lamenting the loss of stocked waters in our national parks, but unless we start paying attention to big picture threats such as coal mining, clearcutting and road building for the fossil fuel industry, there will come a day when, no matter how intently we scan the shoreline, no rises will appear.

Bob Covey // bob@thejasperlocal.com