Skiers, horseback riders and hikers lose out; backcountry lodges forced into disrepair

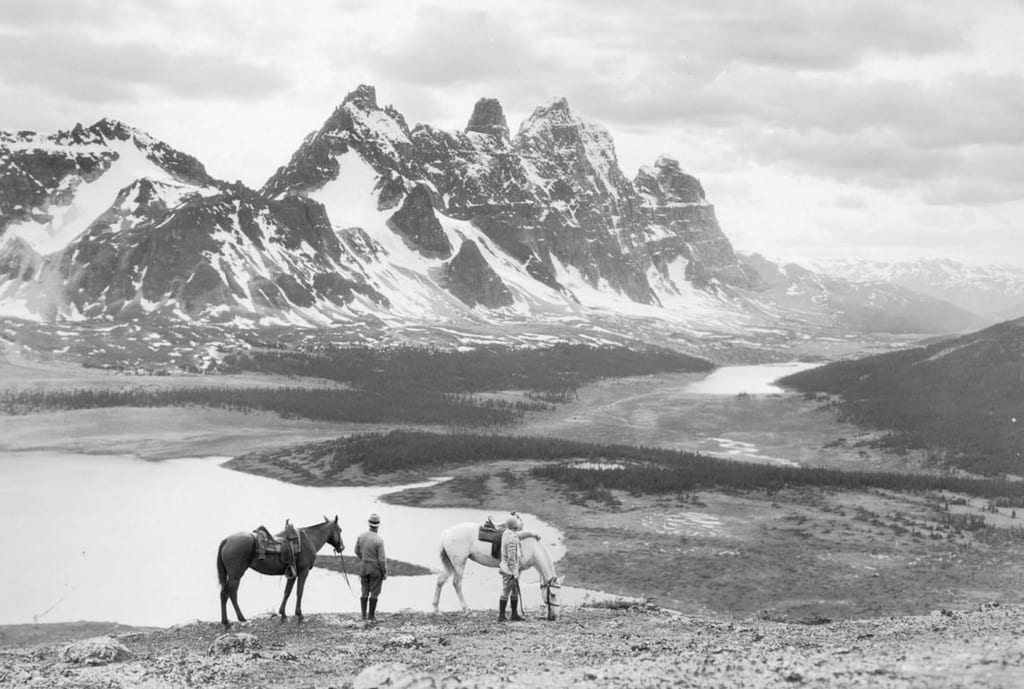

Riding across Maccarib Pass into the Tonquin Valley feels like passing through a mist-filled portal into Narnia, a magical place populated by mythical creatures, including grizzly bears, wolverines and endangered southern mountain caribou. Generations of hikers, skiers and horseback riders have enjoyed the Tonquin Valley and the backcountry lifestyle that goes with experiencing its stunning, remote setting.

Located southwest of Jasper townsite, towards the B.C./Mount Robson Provincial Park border, the Tonquin is known as one of Canada’s premiere alpine regions: a unique combination of barren peaks, ghostly ice and fertile lakes, according to Parks Canada literature. More than 20 kilometres over trails, Amethyst Lake is vast and breathtaking, surrounded by colourful subalpine meadows and backed by the precipitous Ramparts, the jagged tops of which form part of North America’s continental divide.

To access the Tonquin from the Portal Creek trailhead off of the Marmot Basin ski area road, trail users typically climb up through Maccarib Pass, descend into the Tonquin Valley proper, traverse alongside enormous Amethyst Lake’s shoreline, and then descend down the free-falling Astoria River trail, towards Mount Edith Cavell. It is typically a two-to-three day expedition. Hikers, horseback riders—and, in the winter, skiers—have walked, rode and glided along the 44 kilometre Tonquin-loop for the last century in Jasper National Park.

Or at least, they used to.

History fading

In January of 2021, Jasper National Park eliminated the use of recreational horses in the Tonquin Valley—an operational decision, they claimed—then, 10 months later, in October, the federal agency announced the valley would be closed to human access all winter long: from November 1 to May 15, every year. Local trail users were in disbelief. With the stroke of the Jasper Field Unit Superintendent’s pen, the newly-extended restrictions ushered out any winter use in the Tonquin Valley and effectively forced out of business the area’s commercial outfitters, the rich history of horse packing they carry with them, be darned.

“A chapter of mountain history is slipping away,” said Jasper guide and writer, Kirsten Schmitten, who has since created a tribute page to the Tonquin Valley on social media.

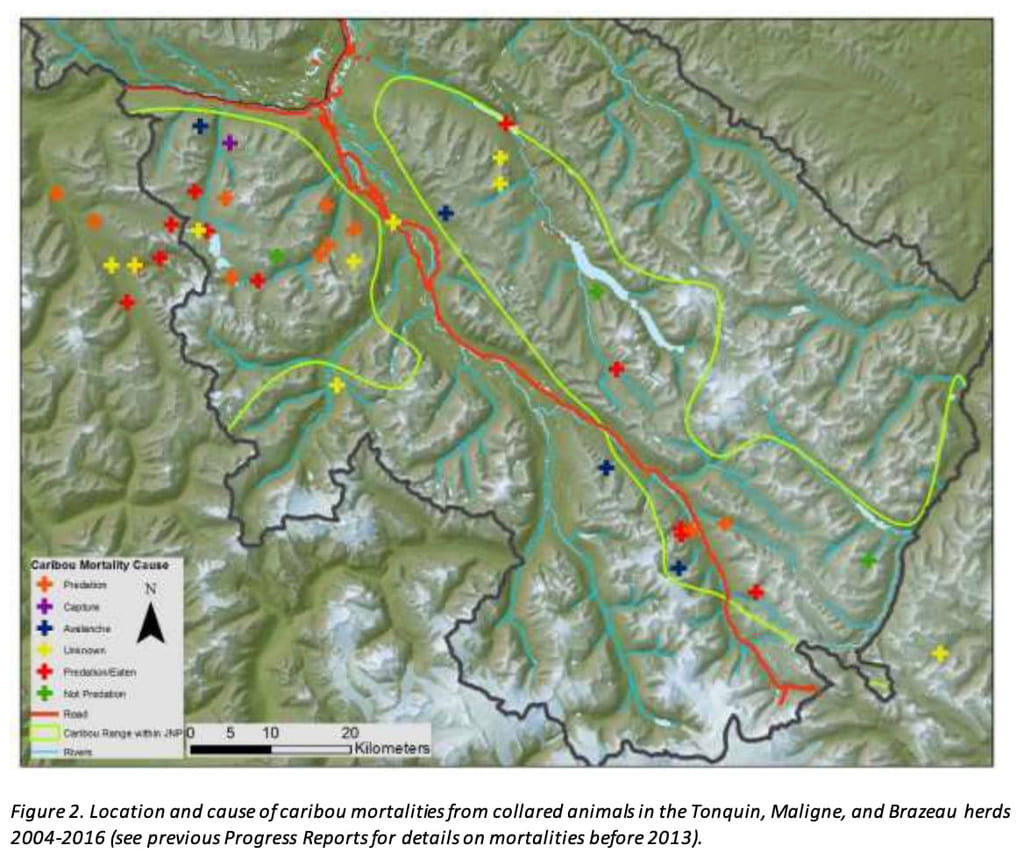

The 2021 closures expanded on earlier measures taken by Jasper National Park in the name of caribou conservation. Largely due to historically mismanaged, and therefore imbalanced, predator and prey dynamics over the last 90 years, the Tonquin caribou herd has shrunk to less than 55 animals. Wolves are caribou’s main predators, and by allowing a proliferation of elk and deer, by shooting wolves in the early days of the park and then reversing their wolf-cull in the late 1950s, caribou populations suffered heavy losses. Other factors at work in the southern mountain caribou’s demise include habitat loss, small population effects (herds being too small to be sustainable) and predator-facilitation.

The winter access closures address this latter threat to caribou. Parks Canada reports that human-set ski and snowmobile tracks (made by recreational skiers and the snowmobiles of licensed outfitters when delivering supplies to their lodges) provide wolves easy travelling. Closing winter access to the valley protects the caribou by eliminating these wolf ‘highways,’ Parks Canada maintains. Some critics have tried to parse the science—suggesting that supporting literature doesn’t differentiate between ski tracks or snowshoe tracks or roads, for example. But the fact is that Jasper National Park has recorded wolves using the trails leading into the Tonquin Valley. According to a 2016 JNP Caribou Program progress report, biologists have hundreds of trail camera photos showing wolves on packed trails. Moreover, using radio collars, Jasper scientists have collected enough spatial and survival/kill site data for both caribou and wolves that they are confident human-made tracks do in fact contribute to caribou predation.

“There is direct evidence of wolf predation on caribou facilitated by packed trails,” Lalenia Neufeld, JNP caribou biologist has said.

Legally compelled

The legal case for putting caribou before recreation and commerce is clear. Southern mountain caribou are listed on Canada’s Species At Risk Act, which obligates Parks Canada to protect their critical habitat. The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society have used their far-reaching voice to show their approval of Jasper National Park’s winter closures, and the Alberta Wilderness Association (AWA) supports access restrictions in the Tonquin, too. AWA conservation director Carolyn Campbell said her organization focused on the “inappropriate continuation of any winter access by people” but also supported a review of human recreation pressures, including backcountry equestrian use.

“Caribou are barely clinging to survival [in the Tonquin], and they have occupied those lands for millennia,” Campbell explains. “We really have to manage and prioritize their survival at this point.”

The AWA’s position on backcountry horse use in Jasper’s Tonquin Valley veers away from their usual stance on the activity. The organization, which was formed in 1968 to defend Alberta’s wild lands, mostly supports horseback riding in wilderness areas, but in this case, sent a strong message to Jasper National Park to reduce recreation impacts.

“We thought there was clear evidence that the valley was too busy for caribou,” Campbell said.

But was it? After all, the reason Jasper National Park has given for discontinuing private horseback use in the Tonquin Valley is the dwindling numbers of those who do it. From 2017 to 2021, on average, only four to nine private horse parties booked backcountry camping permits for all areas of Jasper National Park (not just the Tonquin). That represents a paltry 23 to 102 backcountry riders per year. David Argument, Jasper National Park’s resource conservation manager, said Parks Canada can’t justify investment in trail infrastructure required for horse parties when there is so little use of the trails by these groups.

“We’re prioritizing the larger visitor interest,” Argument explained.

Parks Canada’s numbers don’t wash with the Alberta Equestrian Federation, however. Jason Edworthy, chair of the AEF’s recreation committee, says from everything his organization has seen, trail use by horse riders has actually been increasing, including in the national parks. The discrepancy may be due to the fact that the park’s numbers do not include day riders, who don’t require permits. Regardless, Edworthy suggests the under-estimation of horse use makes it easier for Parks Canada to suggest the activity is not worth investing in.

“It concerns me that private riders who follow all the permits, and might only go in once a year or once every five or 10 years, now don’t have that opportunity,” Edworthy said.

A hole in Canada’s Rocky Mountain history

Not only is the opportunity to experience the historic trails by horseback lost in the Tonquin, it’s also fading fast in other areas of Jasper National Park. Between 2021 and 2022, 10 more trails were added to the list of routes on which no horses are allowed, bumping the number to 47 (out of approximately 150 trails). It’s a trend that disturbs Jasper horse owner and former Parks Canada employee, Wendy Niven.

“There’s no consultation, there’s no communication, and there’s no explanation as to why,” says Niven. “I don’t know why horses aren’t allowed in the Tonquin.”

Argument explained that not all decisions are subject to a consultation process.

“This is simply an operational access decision that was undertaken as part of our general review of activities and access and where we’re investing our efforts,” he said.

Article continues after advertisement

Roofs, lifestyles, caving in

In 2022, for the first winter since before World War II, no humans were allowed into the Tonquin Valley. Jasper backcountry skiers had seen the writing on the wall for some time, but the access restrictions also effectively shut down the two private businesses that were operating in the Tonquin’s 95-year-old outfitter tradition. The October announcement was a death knell to the business models of the wilderness camps. Winter is when the outfitters freight in their heavy supplies, such as firewood, grain for horses and propane tanks. This past winter, the outfitters sustained tens of thousands of dollars worth of damage to their roofs, solar panels and stove pipes because they were prevented from accessing the Tonquin to shovel the heavy spring snow from their buildings. The outfitters’ licences of occupation expire in 2026. Even if the businesses wanted to operate until that time, there’s simply no financial incentive to do so.

The stalemate has trail users speculating on how the situation moves forward. Neither Parks Canada nor the businesses could speak to the potential of Jasper National Park buying-out the outfitters, for example. However, internal documents show that Jasper National Park’s $24 million caribou breeding proposal affords an opportunity to do just that.

“If you are considering spending the kind of money required to build a captive breeding facility etc, maybe you should wrap the cost of buying out lodge owners in the Tonquin? This might be the once-in-a-lifetime window for trying,” reads an internal email obtained through the The Access to Information Act.

“We’re entering those conversations,” an email dated November 21, 2020 responded. “The overall improvement in the Tonquin would be great if we could remove that pressure.”

Story continues after advertisement

Too little too late

Eleven months after that email was written, the pressure was on the outfitters. On October 8, 2021, just 24 days before annual winter access restrictions were due to come into effect, outfitters were told the Tonquin Valley would be closed until mid-May. The announcement put the outfitters in an impossible position. Even if they could pack all of their heavy belongings 20 kilometres overland—a job that would take weeks—there was no way they could get the requisite horse and man-power organized to approach such a task. To emphasize the point, Mother Nature dumped a foot of snow on the trail later that month.

“The announcement was way too late in the year,” said trails ambassador and ski advocate, Loni Klettl. “It wasn’t fair. It wasn’t close to fair.”

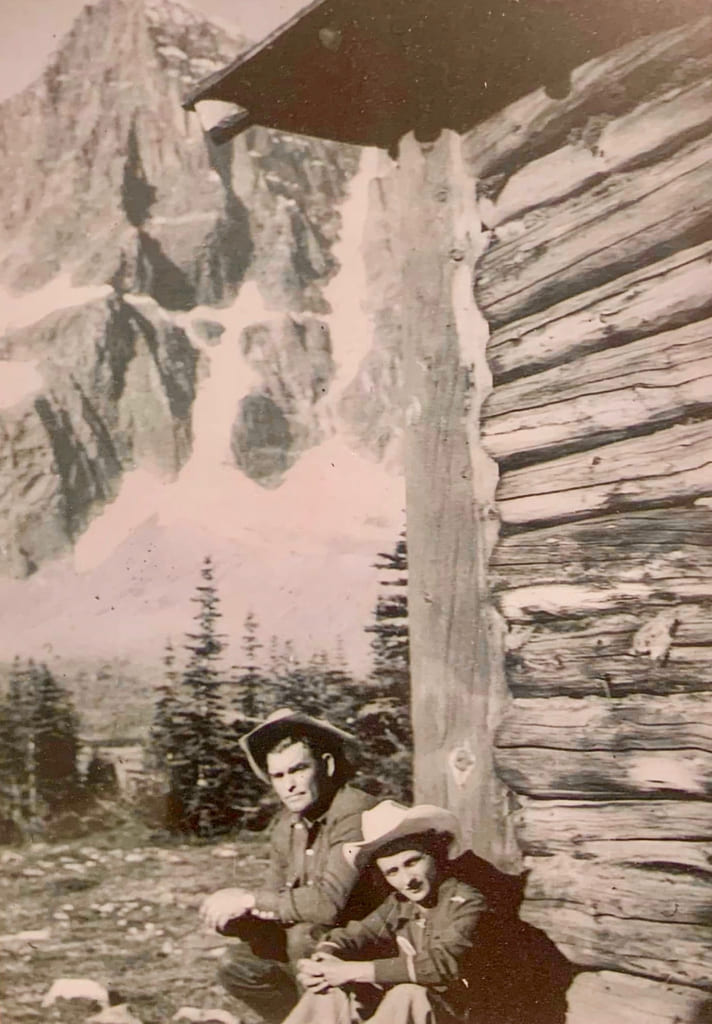

Klettl grew up in Jasper National Park, where her father, Toni, was a park warden. In the 1960s and 70s Warden Klettl oversaw the Tonquin district, skiing into the valley in the winter and using horses to patrol it in the summer. Losing the equine connection to the park’s heritage disturbs Klettl.

“To not be able to experience what people have done for over 100 years? To never have a horse in that valley again? I think that’s horrible,” Klettl said.

It was her dad who, in 1969, wrote up a report on the Tonquin’s declining numbers of caribou and made recommendations to help protect their habitat. Chief among his proposals was for the park to create designated campgrounds (the Tonquin Valley’s five hike-in campgrounds will remain unaffected by caribou closures), outhouses and pack-it-out policies so the hundreds of participants of the enormous tent-camps of the day would no longer run rampant on the Tonquin’s fragile alpine ecosystems.

“He was the first to raise the alarm on the drastic decline of caribou, which in five to six years had plummeted from 180 to 70 animals,” Klettl said. “He recommended a serious study by the Canadian Wildlife Service be a top priority.”

Caribou crisis

It wasn’t until 32 years later, in 2001, that regular progress reports on the state of caribou in Jasper National Park were being published. There have been various efforts to stave off the decline of caribou herds in the Tonquin, Brazeau, A la Peche and Maligne (the last members of which were observed in 2018). Those have included reducing highway speeds, removing artificial food sources (roadkill) for wolves and restricting winter access. Now Jasper National Park is undertaking its most ambitious measure yet: building a facility that, if approved, would breed caribou in captivity. The program’s aim would be to boost the 45-member Tonquin herd to a self-sustaining population of at least 200 animals by 2031.

“We know for a fact if we don’t take action they will disappear,” said Jean Francois Bisaillon, Caribou Recovery Program Manager for Jasper National Park.

If you know, you know

To the average taxpayer, what’s at stake for caribou vastly outweighs the loss of backcountry skiing and year-round outfitting in the Tonquin Valley. It’s a hard truth that passionate trail users and history buffs like Klettl have had to come to terms with. Still, the situation offends a sense of fairness for those whose lives have been enriched by the Tonquin experience.

“If you know these places, you know,” Klettl said. She was standing near the woodshed at the Tonquin Valley Outfitters camp, on almost a century’s worth of woodchips and sawdust. “And those who don’t, will never understand how special they are.”

Earlier that day, with her two brothers, Klettl had watched their friend, Gilbert Wall, lead a pack-string of horses away from his camp. It was likely his last commercial trip, marking the end of lodge-based accommodations and meals. It would mark the end of hikers having their gear packed in by horses—something that allows those with less strength, stamina or experience to enjoy one of Canada’s premiere alpine destinations. It would mark the end of wranglers, guides, cooks and packers, jobs that existed since Fred Brewster built his camp there in 1935. And by Parks Canada’s own admission, it would mark the end of an opportunity for an incredible visitor experience.

“The one downside [about the outfitters being bought-out] is a large caribou herd in the Tonquin would be one heck of a VE (Visitor Experience) offer,” suggested an email obtained through the Access to Information Act.

Creativity shortage

Jasper’s winter habitat closures for caribou conservation ended more than 90 years of backcountry ski trips into the Tonquin Valley and shuttered the two outfitter lodges. After 63 years of maintaining a facility on the north shore of Outpost Lake, the Alpine Club of Canada also closed its Wates-Gibson Hut for future winters. While many Canadians are on-board with the measures, there is skepticism among some recreational users about the certainty Parks Canada assigns to their caribou studies. Edmontonian Scott Meadows said he’s not satisfied that the research has been transparent.

“They could probably have bought the peace, if not the happiness of backcountry users by acknowledging uncertainty and telling us that they’re doing their best in the face of a lot of unknowns,” Meadows said. “Instead, they continue the transformation of Jasper into a place where you’re only welcome if you travel by car or bus.”

Bisaillon, the project manager for Jasper’s caribou program, replied that the public consultation on the closures, and the $24 million breeding facility, has been rigorous.

“We’re really striving to share all the information on our website, through open houses, meeting with stakeholders and providing information in a timely manner,” Bisaillon said.

Last month, before comments closed on the proposed captive breeding project, Jasper hiking guide, school teacher and owner of High Sights Guiding, Jo Nadeau, suggested that there ought to be more creative solutions offered to continue the practice of outfitting in the Tonquin. Instead of pitting trail users and outfitters against Parks Canada, Nadeau offered ideas to collaborate: on helicopter flights, stewardship projects and citizen science initiatives, for example.

“I keep a glimmer of hope that Parks Canada and Jasper National Park will listen to the constructive voices of those who care about the legacy of the Tonquin Valley outfitters and find a creative solution to allow the infrastructure and the experience to remain for future generations,” Nadeau said.

Rush hour

In early August, with the beat of helicopter blades crescendoing over Maccarib Pass, Kable and Sara Kongsrud, who had owned and operated Tonquin Valley Outfitters since 1991, were running on adrenaline. Just one hour earlier, a radio call had come in from Parks Canada. If the Konsgruds wanted their gear flown out of the valley, now was the time. A machine was being contracted for nearby trail work, and there would be no other opportunity for helicopter-assisted freighting.

Overcome with emotion, but desperate to salvage something from their hard-earned assets, the couple, along with a handful of friends, scrambled to drag their camp’s heaviest, saleable items—row boats, a washing machine, chainsaws, mattresses and more—into the meadow beside Amethyst Lake.

“You can’t imagine the pain of these two as they raced around camp, selecting items for the flights out,” said Klettl.

One, panic-stricken hour and three flights later, there was silence in the valley. Kable and Sara looked around, trying to find the words to say a final goodbye—to their outfitting lifestyle, to the history of horse-packing in the valley and to all that goes with it: the cinnamon buns, the fishing derbies, the communal meals, the cribbage games, the cast iron pans, the cowboy coffee.

Time will tell if the day comes when caribou come back to the Tonquin Valley. As for the horses, the wranglers, the skiers, the outfitters and their guests, those days are gone.

Tania Millen and Bob Covey // info@thejasperlocal.com